simply me & the girls, plotting the overthrow of patriarchy + capitalism

how the fashion industry co-opts progressive movements, plus a Girls at Dhabas throwback because why not

Hello to all and Eid Mubarak from this blazing June heat. These days I’m mired in paperwork, logistics, and trying my best to keep my plants from drying out. The world is burning up in every way possible, but the way lawn campaigns have been making the girls sit outside will have you thinking it’s temperate and breezy. Now that we’ve swerved with purpose away from niceties and onto the subject at hand, it’s been a while! What have the girls been up to recently? If the billboards, IG posts and music videos are anything to go by, the girls are going on picnics and riding bicycles. The girls are braiding each others hair and inexplicably playing tug of war. The girls are watching the sunset together, then packing up and making their way home. Its all very Wholesome!

When I say the girls, I am of course referring to the representations of girl and womanhood that have come to pervade our visual culture in Pakistan, and beyond. (If you’d like to read more of my writing on this subject, please see my piece on Zara Shahjahan here)

This newsletter will tackle how these images have changed dramatically over the last ten years, and what this means for the progressive/feminist movements that have ‘inspired’ them. So, first off, how did we get here? How did featuring women in public spaces make its way into so many marketing campaigns? The fantasy of women being outside is actually not a new one in the landscape of Pakistani fashion media. Prior to 2015, I can recall at least one campaign by The Pinktree company in which models adorned in bright colours and gota kaam stand in public places with working class men going about their daily labour cast in the background. Important to note that these women were never loitering or walking, but modeling. The set, including working class men, were merely backdrop, nothing more, but they were ever present. Problematic to begin with, obviously, but this image will also shift.

In 2015 a group of young Pakistan feminists, myself included, started Girls at Dhabas. We were frankly unprepared for the response we would get upon uploading a couple of pictures of women drinking chai at dhabas, and decided to run with it. The premise of Girls at Dhabas was very simple and perhaps its popularity is owed to this simplicity. From our page - Girls at Dhabas is a collective of feminists who are concerned by the disappearance of women and gender nonconforming people from public spaces. We are an open community and wish to define public space on our own terms and whims, to promote and archive women’s participation in public spaces, and to learn from shared experiences. We began to build a feminist archive - mostly on Facebook - posting pictures that women from all over the country began sending us as they sat at dhabas, rode bikes, walked around their cities, sat in parks, and took public transportation. As a collective, we also organised dhaba meetups, study circles and bike rallies. Recent histories of the feminist movement in Pakistan sometimes fail to factor us in, but the truth is that Girls at Dhabas breathed new life into the feminist movement in Pakistan, persuading many to join the cause with its irreverence and resourcefulness. We were also criticized by progressives, liberals and conservatives alike - you could say we united many factions of society in this way. Progressives questioned why middle and upper class women were taking up space meant for working class men, liberals asked why we were not focusing on real issues that women face such as Education, and conservatives wanted to know how we dared to leave the house at all, much less compel other women to do the same.

A note on the criticism by various progressives here, because the figure of the working class man will come up again in this essay. Even though many of the images we received and shared were, yes, of middle and upper middle class girls sitting at dhabas, the collective put out several statements and organized countless events that aimed to dispel the patriarchal notion that working class men are a threat to middle class women. We encouraged women to navigate public space as a way to resist the capitalist expectation that if women wish to go out they must go to a coffee shop or a mall - respectable places where they will spend money. Sharing a public space such as a dhaba or a park did not mean we wished to push out working class men from the few spaces they are allowed to exist in. Many progressives claimed we were making working class men uncomfortable with our presence - to which we responded that this place of mutual discomfort could also be considered productive.

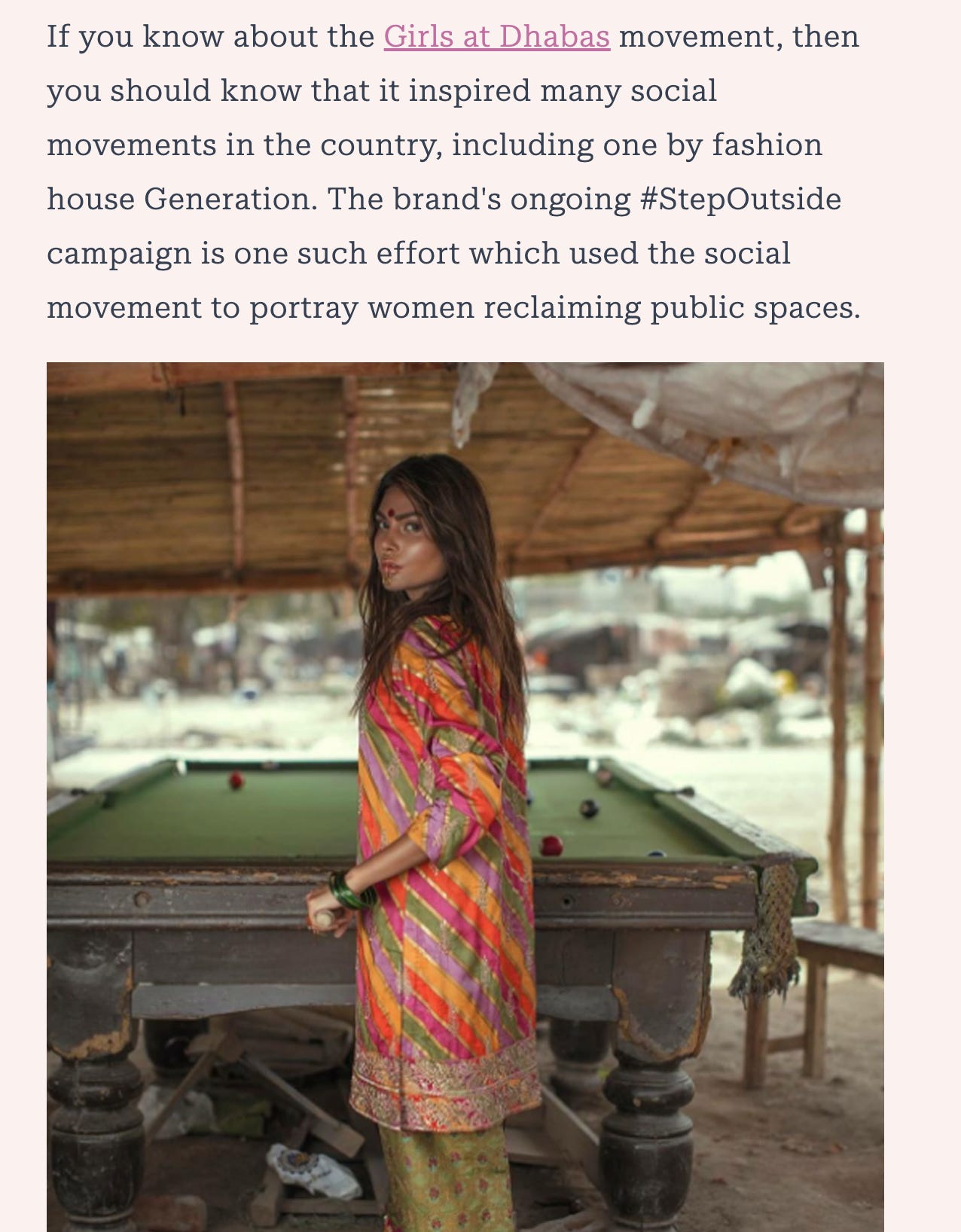

A few months into our organizing, Generation, at the time undergoing a revamp as Khadija Rahman stepped up to the (family) plate, reached out to us, claiming to be inspired by our work and asked if we would like to collaborate with them on a campaign. We decided not to collaborate as this fell out of line with our anti capitalist politics. Generation then went ahead and released a campaign titled #stepoutside - in which a model steps outside her house - plays pool, rides a bike etc. Beyond co-opting the images that had come to be identified with our collective and the movement it sought to catalyse, Generation also made sure to mention Girls at Dhabas in every press piece they did for the campaign. Here are some excerpts from a piece in Dawn Images from November 2016 - about a year after we started Girls at Dhabas

What I want to focus on is why, even though we did not collaborate with them, Girls at Dhabas is mentioned at least twice here and once more elsewhere in the piece. (KR has said in multiple interviews that we appreciated their campaign - which none of us remember doing tbh, so perhaps this was said to preempt accusations of idea stealing) The director goes on to tell us herself that this is because “interest in social causes makes brands noticeable” and gives brands an IDENTITY. Remember, at the time, Generation was actively revamping and setting itself up for the brand it has become today. And so, the co-option of our messaging was key to this revamp. For anyone wondering, of course we were angry. Generation’s campaign implied that our feminist labour was mere fodder that it could dip into at will in order to build a new identity (a rebirth - we’ve discussed several times in this newsletter how capitalism must reinvent itself every few years in order to sustain itself) - that would help drive profit for the brand.

The formula that is starkly revealed to us is is as follows - culture industries watch as people take creative risks, build grassroots communities, work towards progressive futures, and then proceed to use the symbols, images and identities born of our own movements against us. In this case, the site of the dhaba or a public park which Girls at Dhabas viewed as sites of revolutionary potential - spaces where people could navigate their class differences by sharing space- became spaces where only some ‘brave’ women dared to venture because of the potential for danger.

Where are we since #stepoutside and what has changed? In 2024 we are suddenly, as I mentioned earlier, being overwhelmed with images of upper and middle class women enjoying leisure time outside.

(images from Ethnic, Sapphire and Zara Shahjahan)

When I look at these images, I experience the same sort of anger and bemusement I remember feeling when we first saw images of the stepoutside campaign. Besties laying on a blanket outside and reading with a cold beverage? Sharing intimate stories on a park bench? Laughing at an inside joke? If you are as Ferrante pilled as I am surely you also feel similarly attacked. Dear RTW industrial complex, our culture is not your costume! But we’re going to close read a little, so that we can all begin to feel better about this state of affairs. There are two major differences between these campaigns and the 2016 era Generation campaign. The first is the portrayal of behenchara and leisure time. Over the past few years in Pakistan, feminism has become slightly more acceptable in the mainstream - ok no I take that back actually. Since women’s rights have become a more acceptable thing to express concern over, ideas of female solidarity have made their way into our visual culture. Here too, we cannot take credit away from organizational efforts such as Aurat march that encourage women to come together in public every year. Leisure time has had it’s global moment and its repercussions are felt in Pakistan also. Jenny Odell’s How to Do Nothing was huge just a few years ago. Women At Leisure, a popular instagram account that features women across South Asia hanging out, going to the beach, eating ice cream etc has over 35k followers. Across the board, rest is resistance themed content gets a lot of engagement.1 Many of us are thinking back to our childhoods, to our overworked mothers who never sat down and can conclude this idea has some hold to it. Our attachment to leisure then becomes symbolic, we are taking the rest our mothers did not. What follows is a question that has been on my mind a lot; just because we can, does it mean we should?

The second difference is the complete absence of working class men in these RTW campaigns from 2024. Whereas working class men are in the background of most representations of public space. In stepoutside, these men were out of focus, yet present. A woman stands alone in the foreground. Here, however, men are a non entity. In this fantasy of female emancipation, working class men do not exist. Earlier, we concluded that the narrative of stepoutside was to highlight the ‘bravery’ of a woman who loiters the street despite the ‘dangerous’ working class men that loom in the shadows. In 2024, the narrative has changed. The working class man has been completely erased in order for upper and middle class women to come out into public space.

To build on this reading let’s offer another comparison here, one that far surpasses Generation’s 2016 campaign. As my friend Rasti very astutely pointed out the other day, one of the few good iterations of women being in public space within the Pakistani media landscape can be found in the music video of Zahra Paracha’s Bekhudi from 2021. In Bekhudi, women also walk the streets alone. They are shopkeepers, fruit sellers and electricians, they greet each other on the street, hand each other items in the grocery store. But there is more, much more, which is what exactly makes it so good. Bekhudi depicts an economy that rejects capitalism in that it uses a system of barter and not accumulation. You give a fruit, you get a flower. No money changes hands. Even though there are no cis men featured in the world of Bekhudi, the choice to create a system of barter sends a clear message: the reason why women and gender nonconforming people are not free to walk our cities is not because of working class men but because of the intertwined forces of capitalism and patriarchy. One cannot exist without the other.

Coming back to 2024, we see representations of utopia built on a purposeful misinterpretation of how middle and upper class women, often isolated and confined to private spaces, can experience liberation. By simply erasing both men and never directly referencing money in any way, these images detract from the work that feminists do in favour of a meaningless ‘diversity’ style politic. There are countless other examples - such as Generation’s campaign (last year I think) featuring a baraat in which all the ‘traditional male’ roles were instead carried out by women *eye roll* But of course if the critique is aimed towards men with no real power, and money is never called into question then we can all continue as is. Women can go to school, yes. They can leave the home and work, yes. They can even have a picnic outside, as long as they do not question the way the world works.

Ok! We’re close to the end, I promise. The only question that remains is, why bother? If feminist labour is so rapidly and incessantly co-opted by capitalism then how can we ensure our work will not come to nothing? I have in truth read only one text this year with any attention and that is the work of absolute rockstar scholar-artist Ruth Wilson Gilmore. With regards to how to think of collective organizing - “the outcome, rather that the organization (must be) the purpose for its existence,” and, “Many are looking for an organizational structure and resource capability that will somehow be impervious to co-optation. It is impossible to create a model that the other side cannot figure out2” In other words there is no such thing as an ideal or perfect praxis and we should expect this co-optation if we are to keep ahead of it.

She displays this same pragmatism towards images, identities and symbols of resistance (such as women at dhabas, women in parks, women at leisure, watermelons, the radio3) In her essay, “You Have Dislodged a Boulder”, Gilmore writes about a Los Angeles based grassroots organization that she worked with in the 90’s called Mothers Reclaiming Our Children. MROC formed as response to the growing intensity with which the state of California was locking their children into the criminal justice system. For Gilmore, the symbolic power of motherhood was necessary in that moment to “challenge the legitimacy of the state,” but the real work came after. The real work comprised of rejecting motherhood as a form of saviorhood (identity is not considered inherent or pure or natural in any form) and instead encouraging working class women of colour to articulate a critique of the racist, classist prison industrial complex and then go forth and organize in this spirit.

We can see echoes of this in the Baloch resistance movement as well, with Mahrang and Sammi Baloch identifying themselves as sisters of the disappeared and inheritors of broken family lineages. But instead of reifying sisterhood as the only relation of virtue through which justice can be demanded, being the sister of a disappeared brother is used as a mere jumping off point to interrogate and demand accountability from a state that has contributed to the social, political, environmental and economic degradation of the Baloch people.

Hence, images, identities and symbols are merely tools of resistance, nothing more. They serve their purpose for sometime and then are inevitably co-opted. The outcome, as Gilmore reminds us, is what’s important. This really helps put it into context for me. Why bother is hardly the point. What’s next, is the real question we should all be focusing on. We need to move on, and then to move on again. Eventually the work, all the work, will feed into a larger, shared outcome. The task at hand, our shared outcome, is to prevent people from falling into the trap of capitalism and patriarchy, forces that wish to keep us all isolated from one another and unquestioning as a result of it. The simplest way to do this is to demonstrate, as this essay hopefully has, how time and time again regressive forces evolve just enough to show us one representation of progress, such as women being outside, and then attempt to take credit for liberating us all.

Of course, we will not be duped. We know that real change is not bought, but built only when people come together and engage in a politics of refusal against capitalism, and patriarchy. Let them take our symbols. In their hands our images are powerless. Always, always, we must look onward.

If you’ve made it this far, thank you for reading! This newsletter is less than twenty subs away from reaching a thousand subscribers which is honestly so so unbelievable to me. It takes a lot of time, love and labour to write these essays so, if you enjoyed this one and would like to support my work, please do consider sharing on Instagram or Twitter or sending the newsletter to a friend who may also enjoy it.

A couple things to plug:

Operation Olive Branch has put together a master spreadsheet for donations. Please please donate as much as you can. You can find them on Instagram.

Narivaad submissions call: “From Home to Frontiers: Socialist Feminist Struggle in Today’s Pakistan” Submit your pitch to the Women Democratic Front’s first online issue. Deadline is June 25th and we’d love to hear from you! More info here

I have a strong feeling that the days of rest as resistance are numbered. Given Palestine, Sudan, Congo, global recession etc etc the mood around resistance and collective organizing is changing. It’s not chic to be resting too hard rn, and rightly so - capitalism late to the party as always

From “In the Shadow of the Shadow State” - Abolition Geography

See Frantz Fanon’s fantastic essay - “This is The Voice of Algeria” which illustrates how the radio became a tool/symbol of resistance in the Algerian revolution

Eid Mubarak to you too. Thank you for writing this. I've always loved Bekhudi for the very same reasons and because it had that solarpunk energy to it. loved reading this.. Can't wait for the next drop ✨

so good!!! lovely read of RWG too, my absolute fav.